Gorging Yourself Part 2

Big Boy Party. Photo Digby Shaw

Roads are in thin, smooth scabs in compliant earth. Suture-work fencing is pulling the surfaces inwards. Chemistry-set soil leachate agitates raindrops. The hillside scars with exposure burns.

Liquid ghosts vapourise, implode and cough rearwards, propelling two boys in a station wagon, wishing for the best. The air makes eternal sounds, scattering.

The city is serviced by the watershed of the globe, pouring into nodal points. The port lights are hot with the insomnia of trade. Insects mistake this for a thousand different moons and burn their dopey cellophane wings in a million fables with no moral. The sea displaces and palms the hulls and the machines smell of sour, silent corrosion, polished clean by twitching commercial anxiety. The rusty dust is caught by the ancient meanderings of the breeze and becomes undetectable, yet exists as life leaves distorted bodies under buildings after an airstrike.

The boys trip was continuing. We had beer and burgs and chipchips and watched the edge of the earth snuff out the sun and peel back the alternative option of the abyss. They were very yummy. Duppy was hung in the air above us by forced air pressures as tonnes of liquid fuel vapourised around him. He looked out the window and he could see us below him as undetectable swirls, taking our existence on faith. He rubbed his beard, then sniffed his fingies with a smirk.

The bike park in the gorge we were being allowed entry to was a sacred resource. There were three points of novelty:

- It’s large and very expensive.

- One person owns it, among many other things.

- He’s never there, others are rarely allowed.

Duppy arrived wearing a tasseled mum-made jersey with a schizophrenic design and palette; he dragged a big, grey box as he waddled out to the wagon. A little crescent moon of teeth poked out of a beard that sleeved his neck. Picking the scabs off some fresh brew we strapped his Santa Claus Gonstad to the roof of the car, which was worth about ten grand less than the bike + garnishings it was now wearing as a carbon-based hat. We arrived at Hamish and John’s house on dark and scattered gear and food around like dogs weeing on comfortable looking bushes; they tolerated us for about as long as we could tolerate ourselves. I put up a pup tent on the lawn and reclined for my evening hallucinations.

I woke up cold and soggy to the clanging of the maritime economy, the pong of bacon strips, and the stoke of many bros. I slapped the wet tent-flap away and it stuck to the roof with the sound of a wet gherkin slice making perfect face-on contact with a display cabinet window. Tom and Duppy were already squatting outside the tent and offering me a small espresso with sleazy enthusiasm. The coffee was fine, but the boys were addled in a way that would never improve. We sat cross-legged on the stoops and talked about the latest developments in doggo-memes. It didn’t take long for Miguel Hayward to turn up, with wafts of various yeast strains, popped eye capillaries, and a new and unbuilt bike in a box. The general group shook their flat-peaked heads and left in a blur of fluorescent polyesters to catch the shuttle trucks while we waited around for him to put on stickers and drop tiny bolts.

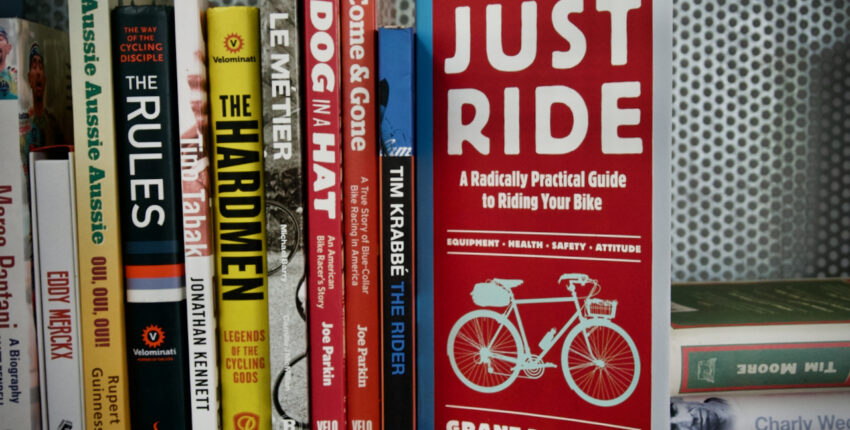

We arrived at the gorge late after a continuous belly-out along the gravel road as our cumulative boy-bulk tortured the wagon’s springs; the weather was looking a bit too good for a sport that I’ve historically disliked roughly 90 percent of the time. I seemed to be the only one feeling this way once we were in the back of the Landcruiser as hundreds of thousands of dollars of bikes banged around on the shuttle trailer and conversations detailed lives that rotated about the central axis of bicycles. I’d ridden a bike about once a month for the last year and was apprehensive about riding a park about which the mountain biking community seemed to have struck a collective agreement that they had to tuck their chins in and lower their voices a couple octaves when referring to it. The main valley dropped away as the trucks ground up the gravel.

A sense of scale was starting to develop, both in estate and expense. Signage, bridges and buildings appeared at the roadside that had a quality and a quantity that was hard to imagine being paid for with the swipe of a single credit card. It was generally recommended not to think on it, so I fiddled with my Swiss cheese kneepads and sipped water from a mouldy Camelbak tube as the dust welled up in the truck.

At the top of the ridge there was a brief briefing and I quietly relegated myself to the back of the fist-pump mega-train for dissenting, medicing and because I was pretty slow. The riding got underway in accordion style; it took the group several punctures, crashes and mechanicals on the first run before things got ironed out. The trails were long, linked, steep and pretty technical; there was a sense that there was quality, flowing riding to be had on them, but the arrhythmic congestion grated like a supermarket aisle. I started backing away and taking off later and the trails soon started to give off their good stank.

One Weird Old Trick

They were unusual artifacts; it was obvious that high-flow sweat had gone into giving them the impression of riding minimally-buggerised natural terrain, sans the unforgiving notes of our favourite brake-line trails dragged into some greasy pine stand that the suburbs didn’t want.

I’d ridden in beech forests plenty and hadn’t seen a trail network use topography and botany to the full intention of this one, but while the tracks and obstacle signage ladled out speed and confidence in dusty plops, they undercut the uncertainty and risk with which riders form relationships with the land. Post-descent impressions of the tracks failed to coalesce and trail names and features were lost as they hazed by predictably. The front wheel was assured contact with a million dollar handshake, funnelled over blind drops and sidling steep banks. Like over-built androids, unsettling in replicating humanity, the tracks tried to recreate nature in a way that is made more obvious by the amount of effort that has been applied.

It’s not to say that it wasn’t fun, but as the ex-builders tooted out cynical jabs at $20,000 corners and broken out rock sections that sucked up months of labour the lustre couldn’t keep its shine against the dulling erosion that the gorge isn’t a community asset, but a plaything built for one person, a neglected toy built by the neighborhood children, laying in the cool dark at the bottom of the box.

It was easy place to like, but a hard place to love.

In a poetic last run the trail bit me. My ungrateful front wheel found itself pitched over the single over-vertical drop in the entire park and I found myself following suit, hitting the engineered gravel with the sound of the bronze Wall Street Charging Bull being airdropped onto a community garden. Everyone was watching; Duppy ran to help me which suggested that it had looked ugly. With claret leaking out of me and my tenderised hams seizing I limped down the hill and was thankful for the $100,000 swing bridge across the river.

I was hungry, tired, sore, and the fellows were trying to force illicits on me. The evening ahead looked plump with potential energy.