What’s that thing they say about the ratio of risk versus reward? That you have to take a chance to make it pay off? Nothing ventured, nothing gained? Cannondale right now would be telling me to shut the hell up, thanks very much.

Like Coca-Cola changing their original recipe, or Michael Jordan attempting to play Major League baseball, some things should just be left as is. Cannondale probably look back at the early 2000s with a deal of remorse, or at least, regret. They took a huge gamble and it nearly spelled the end of the brand as we know it today. Riding on a wave of long term success with their revered and innovative bicycles, they decided to venture into the untested waters of motorcycle production, not just joining the fray but attempting to re-write the book from scratch. History shows that as motorcycle manufacturers, they make excellent bicycle manufacturers.

With rumours of the bike spreading since the late 90s, the pressure was on for Cannondale to get a bike to market in the early 2000s. They promised it would be a game changer, utilising their extensive aluminium manufacturing abilities to produce a revolutionary mainframe which mimicked the new Honda CR250 design from 1997, which also failed to live up to its promise. But Cannondale were in deep, investing more than $20 million into the project and even building a second, dedicated manufacturing plant in Bedford, Connecticut.

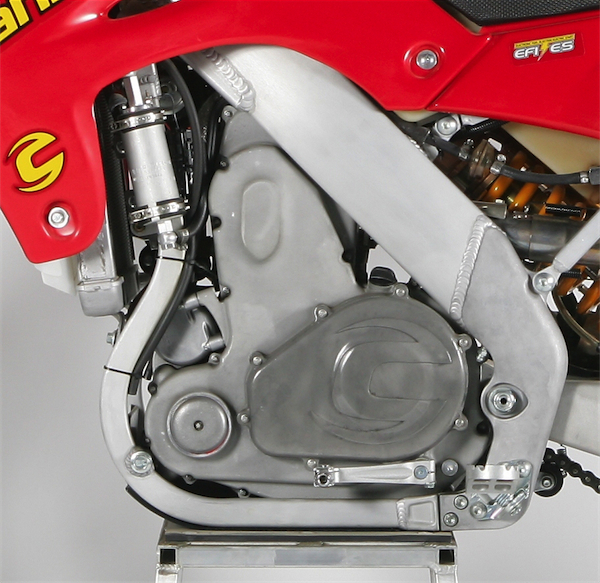

Cannondale enlisted Swedish firm Folan to develop a radical new reverse-cyclinder motor design, incorporating high-end features like fuel injection, electric starting and a quick change “cassette” type transmission. All of these failed in one way or the other, with the bike notorious for breaking down and then being virtually impossible to re-start with the electronic starter, and no kickstarter as back-up. Factory racers would push the bike back to the pits more times than it would make it to the end of a moto. It wasn’t a good look for a company trying to shift big units to the public.

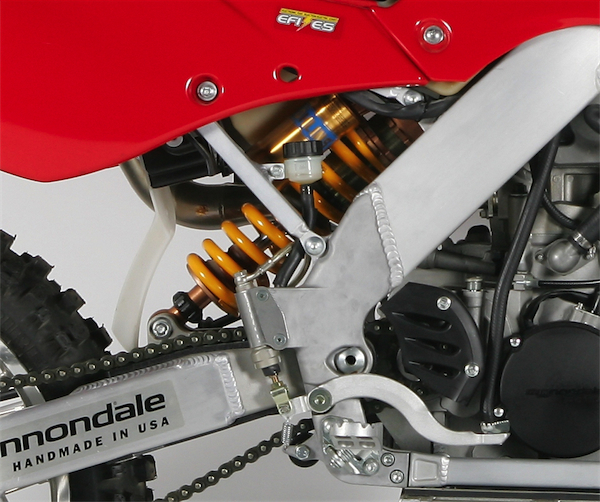

Suspension duties were also given to the Swedes, with super-expensive Ohlins dampers specced at each end. As well as pushing the cost of the bike above all competitors’, it proved to be underdamped and with a no-link system in the rear, just never performed to a level that was expected from such high-end suspension components.

The legendary Jody Weisel from Motocross Action Magazine has ridden just about every bike ever made, and rated the MX400 in his Worst Bikes I Ever Raced article recently. If these words don’t sum up what a manufacturing and financial disaster the bike was for Cannondale, nothing will:

The legendary Jody Weisel from Motocross Action Magazine has ridden just about every bike ever made, and rated the MX400 in his Worst Bikes I Ever Raced article recently. If these words don’t sum up what a manufacturing and financial disaster the bike was for Cannondale, nothing will:

When people accuse me of being unfair to a bike in an MXA test, claiming that I am the reason that the bike failed in the public arena, I always say the same thing: “I don’t make ’em, I just break ’em.” Which leads me to my 2001 Cannondale MX400 experience. I knew this bike was a roach before it was even made. I was friends with former GP rider Mike Guerra, who was leading the Cannondale project. He stopped by early in the project to tell me Cannondale’s plan. Our conversation could be broken down into my three-word replies to everything he told me.

He told me about the copycat 1997 Honda CR250 aluminum frame they were going to use; I said, “That won’t work.”

He told me about putting the airbox in the head tube; I said, “That won’t work.”

He told me about the laid-down no-link rear shock; I said, “That won’t work.”

He told me about the backwards engine; I said, “That won’t work.”

Mike thanked me for the input and never spoke to me again. The 2001 Cannondale MX400 was a bad bike; let me list the ways:

(1) The first test bike we got from Cannondale broke in 15 minutes.

(2) For some reason, every time we rode back into the pits, the Cannondale would flame out about 30 feet away from wherever we wanted to go.

(3) The fuel injection was so strange that we could start the bike in the pits, put it in gear and ride around the track without ever touching the throttle.

(4) When the time came to adjust the valves, we had to get a jack out of the back of our truck and use it to lower the engine.

(5) The oil-in-the-frame chassis got so hot that it would blister our skin if we accidentally touched it.

(6) The electric starter worked in the pits, but when you stalled during a moto—and you always stalled during a moto—the battery would run down before the bike would restart.

(7) The suspension was so soft that it clanged like the bell on Big Ben. Even though one magazine called it the “2001 Bike of the Year,” we gave our Cannondale MX400 back to Cannondale after we got tired of pushing it off the track in the middle of every race.

In 2003 the great moto experiment nearly hammered the final nail into Cannondale’s coffin, when they filed for bankruptcy protection, dropping the motorcycle division altogether and eventually clawing their way back from the brink to their current position as once again a leading bicycle brand. Sticking to what you know may well be their company motto.

Leave a Reply